All about that base: Engineering the Foundation of Distilled Spirits

Where a master distiller sees fermenters, coolers, and spirit stills, engineers see unit operations such as reactions, thermodynamics, and separations. There are many opportunities within a spirit distillery for a design firm to provide insight and efficiency such as utilities, hydraulics, equipment sizing, process safety, and automation. In this series of 7 articles, each article will dive into a single step of the spirits production flow. Each step will explain the technical background or chemistry happening in that step and how Matrix can offer to help.

The Federal Alcohol Administration Act, which was created in 1935 to regulate the alcohol industry after prohibition, defines a distilled spirit as “ethyl alcohol, hydrated oxide of ethyl, spirits of wine, whiskey, rum, brandy, gin, and other distilled spirits, including all dilutions and mixtures thereof for nonindustrial use” (United States). The Alcohol & Tobacco Tax & Trade Bureau (TTB) further differentiates distilled spirits into classes and types for labeling. Each class, type, and end product, have distinct characteristics such as color, flavor profile, aroma, and aging requirements, that set it apart. However, they each follow the same general flow shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Most distilled spirits are manufactured following the same general progression.

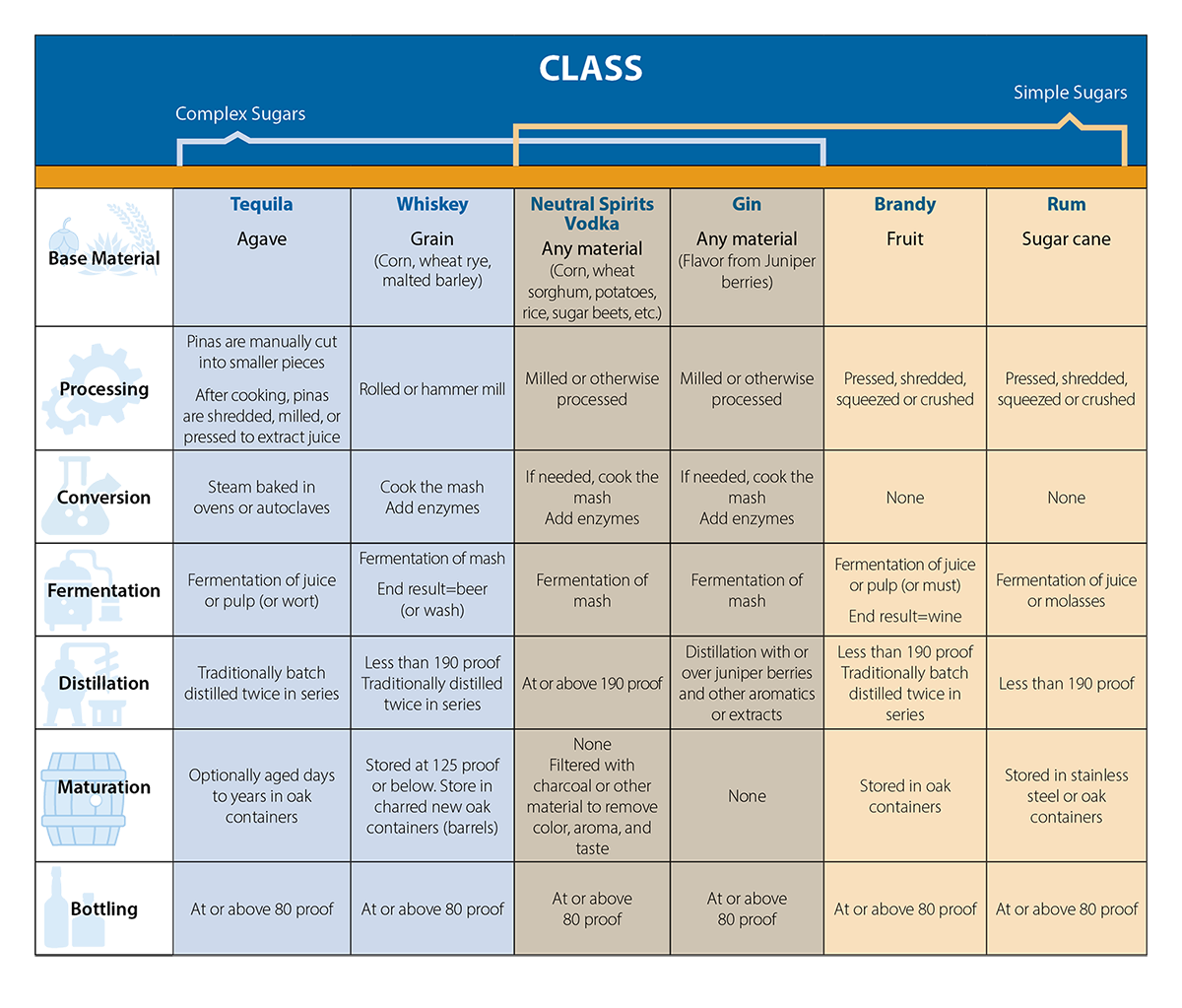

A base material contains sugars, which are made accessible for yeast to digest and convert into alcohol. That alcohol is purified and concentrated using distillation to create a spirit. Figure 2 includes six of the classes recognized by the TTB (TTB) organized by the steps in figure 1.

Figure 2: Six classes of spirits as identified by the Beverage Alcohol Manual (TTB). Each class can have specific requirements for each step of spirit production.

Technical Background

Whether the spirit recipe includes fruits, vegetables, or plants, the process begins with a base ingredient that contains sugar – either in a simple (glucose or fructose) or complex (carbohydrates) chemical structure. The base could be grown on the same property, in the same region, or completely remote from the distillery. The base could be owner grown or provided by a 3rd party. A base could also be an unconventional source of sugar for a distilled spirit like milk or honey.

The base ingredient and where it’s grown or distilled can determine what spirit results from the rest of the process. For example, grain cannot be made into rum. Some products, like tequila, can only be produced in a specific geographical region. In Mexico, that is called a “Denomination of Origin.” A spirit could be produced identically to tequila but if it is produced outside of the specified region, it cannot be labeled as tequila. The resultant spirit could be labeled “agave spirit” or another alternative.

However the base arrives at the distillery, the base is typically unloaded and mechanically transferred to a storage container. This movement could be done with a conveyor, pneumatically transferred, or gravity fed through chutes. Taking grain as an example, a truck may deliver the grain and use a vendor-owned or owner-owned blower to pneumatically convey the grain through fixed tubing into the top of a storage silo.

The design of the base delivery and storage must keep Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and sanitation in mind. Depending on the base material, a shipment could arrive with foreign debris such as metal, stones, or pests. Equipment or procedures should be implemented to prevent foreign debris from entering the storage area.

Once stored, production would draw from the bottom of the storage container to keep the inventory from sitting stagnant. Storage containers should be designed to be fully cleaned, well-sealed, and with the ability to completely empty the container. This will provide sanitary design and avoid pests, mold, or other unwelcome contaminants.

How Matrix can help

The Mechanical team at Matrix has designed numerous material handling systems to safely and effectively move base materials. These material handling systems typically include conveyance (Pneumatic, screw, drag, chain and puck, etc.) Our expertise in careful planning and collaborative designs for limited periods of downtime has decreased installation and startup timeframes.

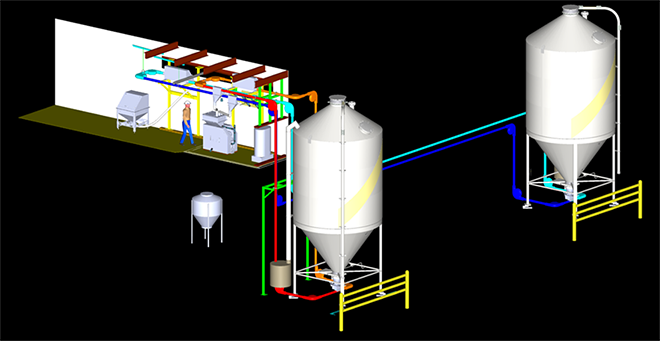

An example of a Matrix project improving the design of base material storage and transport is the installation of new silos for a distillery client. The Matrix team replaced two undersized silos and an outdated screw conveyor system, which was eroding the transport pipe during operation. The two new silos each held more than a truckload of grain, eliminating partial truck deliveries and reducing weekly vehicle traffic. The silos were installed on load cells, which increased the accuracy of grain inventory and consistency of the mash downstream. The new chain and puck system was designed and installed to transport grain for the distillery with less required maintenance. The project design also included dust collection to ensure a safe and clean working environment. This project included engineering, procurement and construction (EPC), allowing Matrix to oversee the project from start to finish and ensure a smooth handover of the turnkey design to the distillery.

Figure 3: 3D design of a silo and grain transport replacement project.

The next article in the series will discuss processing the base material.

References:

TTB. "The Beverage Alcohol Manual (BAM)." n.d. chapter 4

United States. Federal Alcohol Administration Act. n.d.

© Matrix Technologies, Inc.